U.S. Soccer’s problems were apparent long before the final whistle sounded on a 2-1 loss to Trinidad and Tobago that ended the U.S. Mens National Team’s hopes of competing in the 2018 World Cup.

That the U.S. needed a result in the final game of the easiest qualifying group in the world should have already created the humiliation that everyone connected with U.S. Soccer and its fans are feeling the day after.

Failure to qualify is an unmitigated disaster. It’s easily one of the lowest moments in this country’s sports history. But it also may prove to be the shock to the system the U.S. Soccer Federation needed.

U.S. Soccer has stagnated over the last decade. At least on the field. The surprising success of the 2002 World Cup squad, a team that was a controversial refereeing decision away from forcing extra time against Germany in the quarters, never led to the progress we thought it would. Sure, the national team is making more money than it ever did, but the talent pool is still lacking in legitimate world class talent outside of Christian Pulisic.

Unfortunately, Pulisic is the exception and not the rule. He managed to develop into a player capable of competing at the highest levels of the sport despite coming up in a system that has been woefully inefficient at creating such players.

The pool of young talent is probably better than it has ever been, but not nearly as good as it should and can be. Most young soccer players are still being pushed down the youth league > high school > college path. We’re the only country that operates like that in soccer, and the only reason we do seems to be that it’s how our other big sports do it. There’s just one difference: The best football, basketball and baseball coaches in the world work in America. The best soccer coaches in the world do not.

That becomes even more of a problem when the USSF encourages players to stay home and play in MLS instead of challenging themselves in Europe’s superior leagues.

U.S. Soccer’s problems do not start and end at the national level. It’s festering at the lowest levels, where kids are paying to play the sport. In other countries, young talent is recognized early and given all the resources it needs to develop. Until U.S. Soccer starts investing the hundreds of millions it has made over the last few years to create a similar system, the talent pool will never be good enough.

There’s really no excuse for that. Not with a population greater than 300 million and plenty of cash to go around and an ever-growing love for the sport. As Simon Kuper pointed out in Soccernomics, those factors typically lead to success for a national team. But that hasn’t happened in America because the system hasn’t allowed it to.

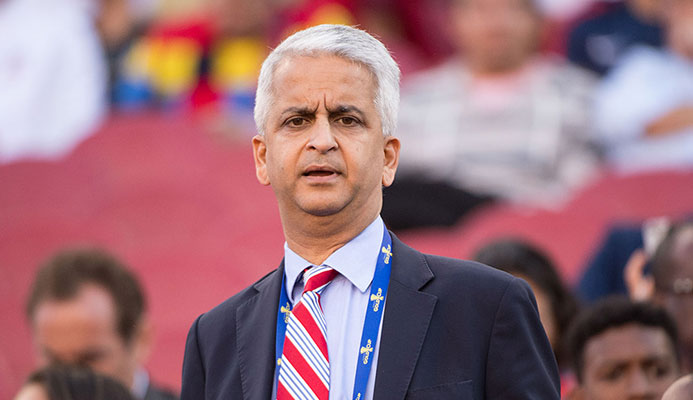

Change is needed. Sunil Gulati, the president of U.S. Soccer, needs to go. Or, at the very least, he needs to change his mindset, which isn’t likely to happen based on his comments after the loss to Trinidad and Tobago.

“You don’t make wholesale changes based on the ball being 2 inches wide or 2 inches in,” he said, referring to Clint Dempsey’s late attempt that hit the post.

Those two inches would not have changed the fact that a country as big as the U.S. needed a last-minute goal to qualify out of CONCACAF. Those two inches wouldn’t change the fact that the team is employing a manager who is out his depth tactically. And those two inches would not change the fact that the national team has one reliable midfielder and an incompetent backline.

Qualifying for Russia would not change any of that.

“Good enough” is no longer good enough. U.S. Soccer should be better, and it’s never going to get there if the goal is to simply qualify for World Cups and keep making money. That seems to be all Gulati cares about. No one noticed because a majority (though that majority is quickly becoming a minority) of the country’s sports fans only cares about soccer every four years.

For the most part, we ignore the sport in between World Cups, but this kind of humiliation makes news. We’re in the middle of the NFL regular season and the MLB postseason, the NBA season start next week and USMNT is the story of the day.

That kind of attention reverses complacency. We’ve seen this before. Think back 13 years ago when the United States basketball team (which we just assumed would dominate forever and ever to the point that we were no longer impressed) failed to win gold for the first since it started sending pros to the Olympics. The humiliation led to wholesale changes for U.S. Basketball. We changed the selection process. We stopped sending hastily put-together all-star teams and actually took the time to build a cohesive roster.

If you’re looking for a soccer equivalent, ask English fans about 1953. When Hungary exposed the English national team and the Football Association was forced to re-think its set-up. The evolution via humiliation led to the country’s greatest sporting triumph: Winning the 1966 World Cup.

A more recent example would be the German Football Association’s 10-year plan, which was developed after a bad showing at the 1998 World Cup and ultimately led to the German’s lifting the trophy in 2014.

We’ve seen this throughout sports history: Humiliation often leads to progress.

Next summer is going to be miserable for American soccer fans. The World Cup will still be fun. It always is. It just won’t be the same without a natural rooting interest. But maybe, just maybe, USMNT’s humiliating absence in 2018 will lead to changes that will give us so much more to root for in the future.