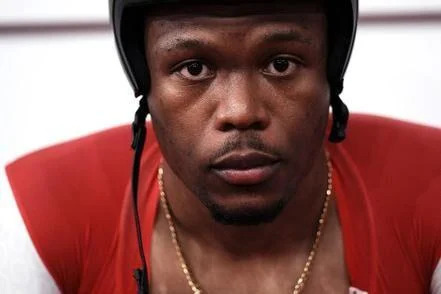

Paul describes his Commonwealth, Pan Am performances; promises more to come.

CYCLING

CYCLING | Trinidad and Tobago Cycling Federation

| SPORT | CYCLING |

| AFFILIATE | Trinidad and Tobago Cycling Federation |

| PRESIDENT | Robert FARRIER |

| SECRETARY | Jacqueline CORBIN |

| CONTACT | (868) 671-8823 |

| MAILING ADDRESS | P.O Box 371 Wrightson Road, Port of Spain Meeting Place: No 5 Yard Street, Chaguaras |

| ttcyclingfederationtto@gmail.com | |

| WEBSITE | www.ttcyclingfederation.com |

SPEED KING MAKES IT three | Local Sports | trinidadexpress.com

Third gold for Paul; Campbell adds silver.

Paul pedals to Pan Am Champs keirin gold | Sports | newsday.co.tt

Nicholas Paul added another medal to his overflowing 2022 tally when he rode to men’s keirin gold on day two at the Elite Pan American Track Cycling Championships in Lima, Peru, on Thursday.

CLASSY NICHOLAS | Local Sports | trinidadexpress.com

‘Happy’ Paul wins double gold at Nations Cup.

Campbell ‘Most Outstanding’ at Grand Prix

Akil Campbell continued to dominate the Trinidad and Tobago Cycling Federation’s (TTCF) Easter Grand Prix at the Arima Velodrome.

Nicholas Paul eyes 2022 UCI Nations Cup, Commonwealth Games

OLYMPIAN Nicholas Paul returns to competitive action, for the first time in 2022, at the International Cycling Union (UCI) Nations Cup in Glasgow, Scotland from April 21-24.